|

|

History of the Chartres Expedition |

Map of the Expedition |

Documents Relating to the Occupation |

Biographies of the expedition's Officers

Following the Treaty of Paris ending the Seven Years War, the

French surrendered the Illinois country, along with most of its holdings

in North America. Located along the Mississippi in present-day southwestern

Illinois was

Fort de Chartres, the French headquarters in the Illinois

country.

Immediately, British forces occupied all French military posts, with the

notable exception of Fort de Chartres. The British military was preparing

to send an expedition to Chartres to relieve the French garrison, but the

Indian uprising led by Pontiac consumed most of the British attention.

In 1764, men from the 22nd and 34th regiments traveled up the Mississippi,

as far as 250 miles from New Orleans, only to be attacked by Indians, prompting

the entire expedition to turn and flee back to New Orleans.

The failure of the Mississippi route prompted the British leadership to plan

an alternative route: travelling down the Ohio river from Fort Pitt,

moving swiftly to prevent marauding at the hands of the area's Indians. Over

the winter of 1764-1765, Lt. John Ross of the 34th Regiment and

Hugh Crawford, a trader, set out to notify the commandant of Fort Chartres

of the intentions.

Following is a chronology of notable events and locations surrounding the expedition to Fort

de Chartres. Journals were kept of this expedition by Captain Stirling, and either Lt. Eddington or the surgeon. When relevant, the author will be noted. Information from sources other than the journals will be noted.

Thomas Stirling

- January, 1765

- Noted frontiersman and Indian trader George Croghan is dispatched to Fort Chartres, to negotiate a treaty of peace with Illinois country Indians, following a route from Fort Pitt, along the Ohio River, to the Mississippi and Fort Chartres.

- March 22, 1765

- While Croghan is waylaid by frontier marauders, Lt. Alexander Fraser of the 78th Highlanders takes off on the expedition without him. Fraser is accompanied by (among others) a sergeant and eight or nine men of the 42nd.

At Fort Massac, Fraser sent the sergeant, an Indian, the interpreter, and six soldiers with the batteaux down the river towards Chartres, while he and the rest of the party continued on towards Fort Chartres overland.

- April 17, 1765

- Fraser's expedition arrives at Fort Chartres. Fraser and his party were imprisoned several different times by different Indian groups, finally released after intervention by Pontiac himself.

- May 14, 1765

- Croghan, after resupplying his expedition, and gaining the cooperation of the Shawnee and Delaware Indians, departed for Chartres.

Ouiatenon, on the Banks of the Wabash

- May 19, 1765

- As the situation at Chartres takes a turn for the worse, Fraser sends his men down river to New Orleans.

- May 29, 1765

- Fraser makes his own way to New Orleans.

- June 8, 1765

- At the mouth of the Wabash, Croghan's party is attacked and looted by Kickapoo and Mascouten warriors. The party was then imprisoned at Fort Ouiatanon in Indiana. Upon realization that such powerful tribes as the Shawnee and Delaware were in the party, the looters were repentant, releasing Croghan and his party.

As the expedition prepared to continue on to Fort Chartres, Pontiac arrived, announcing that he and the Illinois were willing to make peace.

- June 19, 1765

- Fearful for their safety, Fraser's expedition departed from Fort Chartres, and arrived in New Orleans on this date.

- July 12, 1765

- Croghan writes Fort Pitt, informing them of his capture, and of Pontiac's peace offer. An expedition was immediately put in motion to relieve Fort Chartres, and occupy the Illinois country.

- August 24, 1765

- The 42nd Regiment (The Royal Highlanders) was selected for the

expedition, commanded by Captain Thomas Stirling, who would later serve as

commanding officer of the 42nd during much of the American Revolution. The

expedition consisted of three lieutenants , a surgeon's mate, four

sergeants, four corporals, two drummers, 92 private soldiers, one bombardier,

four matrosses, two Indian interpreters, and twelve Senecas and Delawares

acting as scouts.

The lieutenants were James Eddington, James Rumsey, and John Smith.

The names of the rest of the expedition are unknown, except for

Sergeant MacIntosh, who drowned very early in the

expedition, and the bombardier, whose name (written as Covin) is most

likely Cowan or Gowan.

- August 24, 1765

- Capt. Stirling notes that the first night of the expedition at Beaver Creek, one sergeant (McIntosh) "drank too freely" and fell out of the boat and drowned. Eddington states that McIntosh fell in and drowned trying to "push the Battoe he was in off a large Rifft where she had grounded."

- August 26, 1765

- Expedition at Yohaistoe Indian town. Private Robert Kirk (in Through So Many Dangers: The Memoirs and Adventures of Robert Kirk, Late of the Royal Highland Regiment), describes that the Highlanders had a war dance with the Indians.

Ohio River at

the Muskingum

- August 30, 1765

- Encamped at the mouth of the Little Kanawha river.

- September 1, 1765

- The expedition kills and takes for food a "Buffaloe Cow, which made a fine meat as ever England produced.". Eddington notes that they left half the carcasses where they lay, with nothing more than their tongues taken. The journal notes many buffalo hunts throughout the trip.

- September 2-3, 1765

- Encamped at the Kanawha river. Eddington describes the expedition's guard mounting process and readiness should they be attacked while underway.

- September 3, 1765

- Stirling fashions colors of a table cloth, with a red cross made from Indian paint.

- September 7, 1765

- Expedition encamps at the mouth of the Scioto river. Eddington describes Lower Shawnee Town upriver.

- September 10, 1765

- A windy day, the expedition cut masts and made sails of the men's plaids.

- September 11, 1765

- Expedition passes Miami river.

The Falls of the Ohio

- September 15-17, 1765

- Expedition unloads battoes to pull over the Falls of the Ohio, then re-loading. Spent the 17th repairing Battoes. Left a marker on a tree with the name of the regiment, date, and names and number of the men in the expedition.

- September 22, 1765

- Capt. Stirling has a stirring battle with a bear.

"About one o'clock seeing a large Bear swimming across the river I made the rowers pull hard to come with him before he landed, but he had got ashore before we came up. However, as he stopped on the shore to draw breath & look at us before he went into the wood, I took a shot at him & hit him but did not kill. Jumping ashore, I pursued him as he ran into the wood with my bayonet fixed & just as he was scrambling up the bank came up with him & ran the bayonet into his posteriors & followed him into the wood. Finding he could not make his Escape, he turned upon me very fiercely & raising himself on his hind feet advanced upon me. I, trusting to my bayonet, stood my ground & drove it up to the Muzzle of the piece in his breast but that, far from killing him, enraged him the more. Laying his fore paws across the gun, he snapped the bayonet in two & ran at me. I had then nothing but my heels to trust, which would not have saved me from his merciless paws, as the Slipperiness of the ground retarded my flight, had not two of the soldiers followed me with setting poles in their hands. Seeing my danger, they ran up to assistance, by labouring at the Bear with the poles till he turned upon them, which gave me the time just to throw cartridge into my fuzee & shoot him thru the head, as he was standing on end to seize one of the men. He was a monstrous Creature. I had him skinned. He measured above 6 feet long."

White Pelicans

- September 24, 1765

- In southern Indiana, the expedition encountered a "prodigious number" of pelicans, which all writers took time to record in great detail.

- September 25, 1765

- The expedition passed the mouth of the Wabash. Both journals mention its outposts, including Ouiatanon, where it is described by Eddington as having "vast & extensive plains or Meadows on its banks, abounding with incredible quantities of all kinds of game, and several numerous Tribes of Indians live on its banks: the Piankashaws, part of the Kiquapous & Musqatons [Mascouten], Ouiatanons etc.."

Eddington notes that the from the place where the Wabash joins the Ohio, the French refer to as the Wabash, with the Ohio ending at the Wabash. The British, though, call the whole river from Fort Pitt to the Mississippi the Ohio.

Three Indians are set forth to Fort Chartres overland to warn the French commander of the expedition's imminent arrival.

Cave in Rock

- September 26-27, 1765

- After discovering a Battoe belonging to Croghan, the Highlanders discover a cavern (today's Cave in Rock State Park), corroborated by Kirk, who erroneously recalls it much earlier in the journey. Eddington notes graffiti on the cave walls from French officers and traders that was already as old as 30 years. The expedition then encounters a group of voyageurs and a notorious Shawnee chief named Corn Cobb, (aka Charlot Kaske) who were carrying "one thousand weight of powder, a considerable quantity of lead, and a good number of Muskets." Corn Cob did not believe that Croghan had made peace with his people, and was openly hostile to the British, who he called "a greedy & encroaching people." On the 27th a council was held with Corn Cobb. Corn Cobb's own brother was killed in the attack that led to Croghan's capture and imprisonment at Ouiatenon.

Stirling notes that his distrust of Corn Cobb was well founded, as Croghan later wrote that he was a "bad and useless man; has been much in the French interest". Stirling also later reveals that part of Corn Cobb's dislike of the British was likely due to a fear that the British would take his wife, a white girl who had been kidnapped from Virginia. (In the peace treaty made during the Muskingum expedition, Bouquet had ordered that all captured white people be delivered by the Indians.)

Kirk, in Through So Many Dangers also describes this encounter. Lt. Col McCulloch speculates that Kirk was either within earshot of the interpreter or still had knowledge of Shawnee from his own period of captivity.

Fort Massac, viewed from the Ohio

- September 28, 1765

- Expedition encamps just past the Cumberland river. Eddington describes a conversation with a French officer here who claimed to be one of those who traveled into Tennessee to supply the 1760 siege of Fort Loudoun.

- September 29, 1765

- The expedition arrives at Fort Massac, which was burned to the ground six months before by Indians. Stirling describes some of the history of the fort. Lieutenant Rumsey sent ahead to Chartres overland with a soldier, a couple of Indians, and an interpreter.

- September 30, 1765

- The expedition reaches the Mississippi, where all journal authors note the differences between the rivers: the clear Ohio didn't mix into the clay-colored, muddy Mississippi for over a mile past the confluence. The speed of the Mississippi's current drug the expedition downstream, despite the hard rowing of the men.

Confluence of the

Mississippi and Ohio

- October 3, 1765

- The hard work getting up the Miss is si pi results in broken oars - much of the day spent fashioning new ones. Expedition finds an island, where they found the remains of an earthern Indian fort, from a battle where Cherokee attacked Illinois and Kickapoo.

- October 7, 1765

- The expedition reaches Kaskaskia. The entry from October 6 and 7 note that they were constantly on the lookout for Lt. Rumsey, who had been ordered to get a canoe and come back to join them.

- October 9, 1765

- The expedition passes Ste. Genevieve, noting the "pretty Girls" there.

Through the front gate

The expedition was received by the French garrison. Stirling notes that the French commandant requested permission to stay at the Fort, to which Stirling agreed, provided that the 42nd took poses si on first.

Eddington notes that the British and French officers dined together that night.

- October 10, 1765

- The 42nd takes possession of Fort de Chartres. Stirling notes that St. Ange (the commandant) insisted that the striking of the French flag would have to be done by the British, since he would never lower the Pavillion Francois. Following is the entirety of Eddington's journal entry for October 10:

"The men being all properly dress'd, we got under Arms about 10 o'clock and march'd to the Fort with our Drums beating. Before we came to the Gate an Officer with a party came out of the Fort and planted himself on the Road some distance from our Front. Our Detachment immediately halted and an officer with a party went forward to him. The French Officer challeng'd "Who's there", "What Regiment" and what we were marching for, all which being matter of form. We having hanswer'd to each challange he call'd to us we might advance. We accordingly resum'd our March and found an Officer Guard drawn up at the inside of the Gate, with rested Arms and a Drum beating a March as we passed on to the Square."

"There were about Forty French Soldiers in the Colony, --- I was sent with the Officer at the Gate, with the same number of Men to relieve him. His Guard was compos'd of old Men looking like Invalids without any sort of uniform. Most of them had on Jackets of different colours and slouch'd Hats, and their Arms seem'd to be old and in very indifferent order. When the Sentries were relieved and the Guard just ready to march off, The French colours were pull'd down. Upon sight of this those Honest Old Veterans were greatly Chagrind. They could not help venting their indigination, by shrugging their shoulders and declaring when they fought under the Marshals Berwick Saxe and Lowendale, no such dishonour was then ever seen. In fact, all Europe trembled at the French name."

The verbal hand over of the fort began as follows:

Verbal process of the cession of Fort Chartres to Captain Sterling of His Majesty's 42d Regiment, appointed by General Gage, commander-in-chief of all His Britannick Majesty's Forces in America.

"This 10th day of October, 1765, We, Louis St. Ange, captain of Infantry and Commandant of the said Fort Chartres, on the part of His Most Christian Majesty, and Joseph Fievre, King's Commissary, and Store keeper of said Fort. In consequence of the Orders We Have received from Monsieur D'Aubry, Chevalier of the Royal and Order of St. Louis, Commandant of the Province of Louisiane, and Foucault, commissary Comptroller of Marine and Ordannateur in said Province; We deliver to Monsieur Stirling aforesaid the said Fort Chartres ... [ detailed description of the fort ]

Which Buildings and Fortifications, we the above named Officers have delivered into the Hands of Monsieur Stirling, appointed by His Excellency General Gage Commander in Chief of all His Brittannick Majesty's Forces in America.

Fort Chartres 10th Octor, 1765,

(Signed) St. Ange Le F1evre.

Thos. Stirling.,

J. Rumsey,

D Commissary.

(Carter, p. 201)

the entirety of the description of the fort can be found in "A New Regime, p91.

- October 11, 1765

- The men spent the day cleaning the Fort and Barracks, which were "very dirty." and "very long weeds several feet high were growing all over the Square and round the wall.

French Marines drilling at Fort De Chartres

(Tippecanoe Ancient Fife and Drum Corps)

- October 14, 1765

- The inhabitants of the colony were taking their cattle, grain and effects across the Mississippi to the Spanish side (St. Louis). Houses were even torn down and their materials used to build in Spanish territory. Despite British proclamations and prohibitions, residents continued to clandestinely sneak off.

- October 17, 1765

- A letter from Eddingston records that the expedition has

"got peaceable possession of one of the prettyest Stone Fort I ever saw, though that is indeed saying all of it, for we neither found Ammunition nor any other Stores that are usually expected in such a place, and if everything of the necessary kind can't be got before the Spring which is the great time of the Indians to come to trade, and should they take anything in their heads the Garrison must be left to their mercy, and what can One hundred men do without Provisions against three or four thousand Indians, but this is only the worst side of things, and now for the Inhabitants and Country, etc.

(Carter, p. 201)

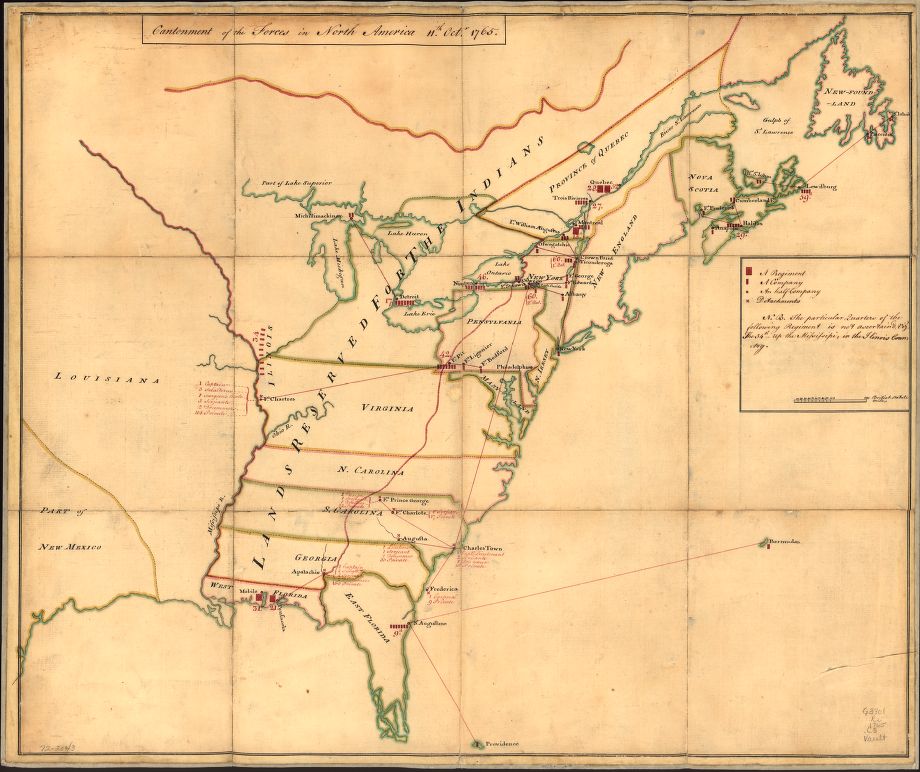

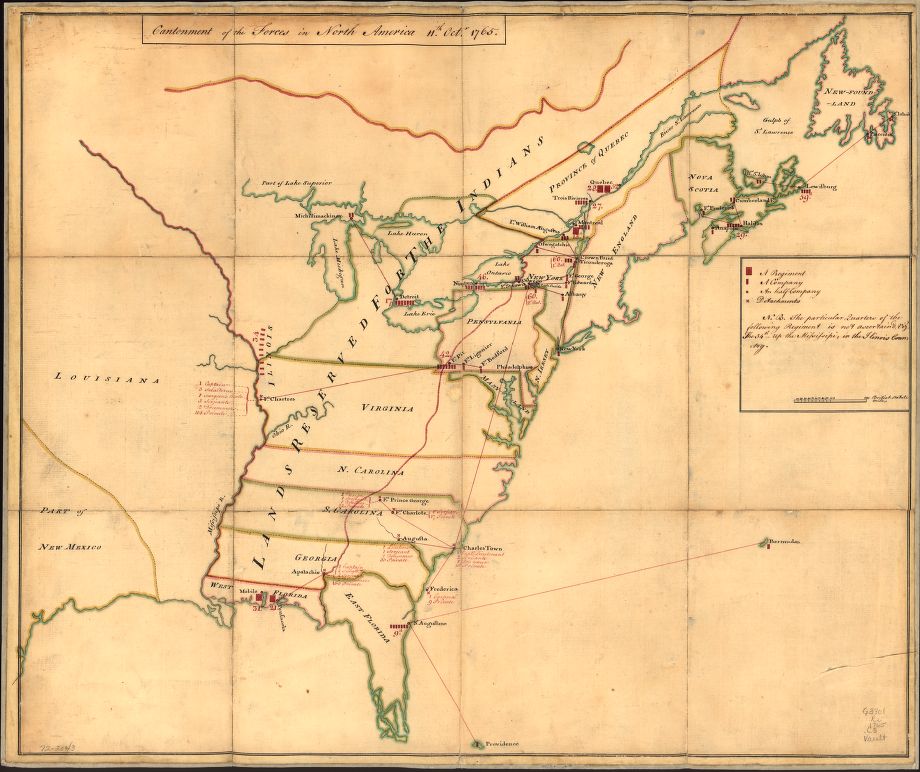

Cantonment of the forces in North

America 11th. Octr. 1765

- October 18, 1765

- 42nd is low on powder and ammunition. Some debate as to ownership of artillery and powder in the fort - the British and French interpret the terms of the treaty differently. In a letter to Gage, Stirling notes:

"When I left Fort Pitt Colonel Reid did not think it Necessary I should have much ammunition with me, as I should find it here, therefore gave me little more than sixty rounds.... St Ange just now put a Protest in my Hands against my taking the Powder which is contrary to His Instructions, and when I expostulated with Him about it, He told Me it was only to exculpate Him in case He should be found Fault with, by disobeying His orders."

(Alvord, "The New Regime" p.110)

- December 2, 1765

- Stirling and 42nd relieved by Major Robert Farmar and the 34th.

- December 17, 1765

- Stirling writes to Gage - notes that St Ange and the French withdrew to St Louis on Nov. 23rd. Also describes the need to rebuild Kaskaskia, the current fort being "ruinous, ill situated, and no water", and to build a fort at Cahokia opposite the Spanish settlements, and near to ferries. Tells Gage that the Miss is si pi will likely carry away Chartres in June.

In a separate letter to Gage on the 19th, Major Farmar of the 34th reiterates that the fort will likely be flooded out.

(Alvord, "The New Regime" p.125)

Later parts of Eddington's journal details the surrounding territory, including settlements, wildlife, plants, fruit, fossils, and the area's topography. On January 5, 1766, the 42nd arrived in New Orleans, sent that way rather than back to Fort Pitt due to the lack of provisions for such a journey (Alvord, "The New Regime" p.133). The expedition arrived in New York on June 15, 1766 by way of Pensacola, at which point they marched for Philadelphia to rejoin the regiment.

In Philadelphia, the men of the de Chartres expedition were commended in the Regimental Orders of October 16, and Stirling's company was mustered in 1766 at a strength of 37 men.

Stirling's Co

muster roll, 1766

Courtesy UK National Archives

Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Robert G. Caroon's "Broadswords and bayonets : the journals of the expedition under the command of Captain Thomas Stirling of the 42nd Regiment of Foot, Royal Highland Regiment (the Black Watch) to occupy Fort Chartres in the Illinois Country, August 1765 to January 1766"

This timeline of the Chartres expedition is summarized from that same volume.

Following the departure of the 42nd, the fort (now dubbed Fort Cavendish by the 34th in honor of its Colonel, though it didn't stick - Gage continued to refer to it as Chartres) was garrisoned first by the 34th Regiment of Foot, and then by the 18th (Royal Irish), who would remain at Chartres from 1768 through 1772, when Chartres was vacated - leaving control of the Illinois country at Kaskaskia.

View The 42nd Highlanders in North America in a larger map

From the Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Library for the year 1907 - includes letters from Eddingston, Stirling to Gage, the French Commandant to Gage, and an inventory of the Fort.

Following

are brief biographies of the expedition's officers graciously contributed

by the Black Watch of Canada's Lieutenant-Colonel Ian Macpherson McCulloch.

James Eddington |

John Smith |

Thomas Stirling |

James Rumsey |

James Eddingstone

was the Adjutant and second-in-command of the Stirling

Expedition. Born in Scotland in 1739, Eddington was commissioned Ensign

in the 1st Battalion of the 1st or Royal Regiment of Foot, 2 March 1757.

Later in 1757, he transferred to the 2nd Battalion of the Royals and came

to America with the regiment. He was wounded during the battle of Echoe

[Tessuntee] in Montgomery's campaign in the Carolinas in 1760.

He was gazetted Lieutenant in the 42nd or Royal Highland Regiment of Foot, 9

July 1762, and by 1765, was in command at Fort Loudon before being

handpicked as one of four officers suitable for the Stirling Expedition.

Eddington returned with the Royal Highland Regiment to Ireland in 1767, but

left the British army, 10 February 1770. He then started a second military

career in the service of the East Indian Company army rising to the rank of

Lieutenant-Colonel. He died in 1802.

He is listed as Edington in WO 34/47: ff. 17-18 and Eidingtoun in WO 25/209;

WO 25/209: f. 159; land grant in "The Towns of Windham County", Vermont

Historical Gazeteer, Vol. V, (Brandon, 1891). David Stewart of Garth,

Sketches of the Highlanders of Scotland, Vol.I, (Edinburgh, 1822), 355, 359

[hereafter Sketches].

John Smith

(1732 -1783). British army officer.

John Smith was born in Scotland in 1732 and joined the 42nd as a gentleman

volunteer c. 1755. He was made Ensign in the 42nd Highland Regiment, 15 May

1757, while it was still stationed in Ireland and preparing to go overseas.

He was wounded at the Battle of Ticonderoga, 8 July 1758, and two weeks

later was promoted to Lieutenant (26 July 1758) in room of one of numerous

regimental officers killed, Lieutenant Hugh Macpherson. Smith served on all

subsequent campaigns of the regiment: Ticonderoga and Crown Point 1759,

Montreal 1760, the Carribean 1762. He was with the remains of his regiment

that marched with Bouquet to relieve Fort Pitt and fought with Kirkwood at

Bushy Run in August 1763. On the downsizing of the 42nd Foot to peacetime

establishment in September 1763, he was retained as one of the more senior

and veteran lieutenants of the regiment and was entrusted with the command

of Fort Ligonier 25 December 1763 - 2 March 1764. In the fall of 1764, Smith

participated in Bouquet's Muskingum expedition to chastise the Ohio Indians.

In 1765, he served as Captain Stirling's second-in-command on the

expedition down the Illinois to secure Fort de

Chartres and its dependencies for the British Crown. On his return from the

expedition, Smith was hard-pressed financially, as were his brother

officers, but he kept his commission and returned with the 42nd to Ireland

in 1767. He was made Captain Lieutenant, 14 January 1775 and was promoted

Captain, 16 July 1775, with seniority to the date of his Captain

Lieutenantcy. He served as a company commander for the duration of the

regiment's service in North America during the War of Independence. He died

[dd] 26 July, 1783, 26 years to the day of his promotion after the battle of

Ticonderoga. Bouquet Papers, VI; BALs; Officers of the Black Watch 1725 to

1952(Perth, 1952, [revised edition]); BM, Add. MSS. 21651, f. 114; "Monthly

Return of HM's Forces in North America" dated 21 February 1766." WO 17, NAC

Microfilm B-1566.

Thomas Stirling

or Sterling [8 October 1731-9 May 1808] the captain

commanding the expedition to take possession of Fort de Chartres.

Stirling was the second son of Sir Henry Stirling of Struwan and Ardoch.

He was commissioned Ensign in the Dutch service, 30 September 1747 and was

placed on half pay in 1753. He was restored to service, as Ensign in in

the 1st Battalion of Colonel Marjoribanks' Regiment, 31 October 1756. In

1757, three additional companies were added to Lord John Murray's 42nd

Highland Regiment of Foot and, on the recommendation of the Duke of

Atholl, and having raised the requisite number of men, Stirling was

gazetted Captain, 24 July 1757[although the 1st BAL 1763 has the year as

1756]. In November of that year, he sailed for America. In garrison at

Fort Edward, he was not present at the 1758 attack on Ticonderoga. He

served with the 42nd in the 1759 and 1760 campaigns with Amherst. He took

part in the capture of Martinique in 1762 and was wounded, 24 January 1762

[WO 34/55: f. 58] but was able to serve in the capture of Havana later in

that year. He returned with his regiment to America and in August, 1765,

was sent in command of a company to take possession of Fort de Chartres on

the Mississippi. In 1767, the 42nd left America for garrison duty in

Ireland and Scotland. On 12 December 1770, Stirling was gazetted Major to

the regiment [although that appointment is not recorded in BAL 1770 or BAL

1771], and on 7 September 1771 was made Lieutenant Colonel. When the War

for Independence broke out, Stirling raised the strength of his regiment

from 350 men to 1200 in five months, returned with it in the following

spring to America, where he commanded it continuously for three years

during the war. He was badly wounded in 1779 and was invalided home. He

was made Colonel by brevet, 19 February 1779 while continuing to serve as

Lieutenant Colonel in the RHR. He was also made Aide de Camp to His

Majesty the King. Stirling was made Colonel of the 71st Highland Regiment

of Foot, 13 February 1782 and was made Major General, 20 November 1782. He

wnet on half-pay when the 71st was disbanded, 4 June 1784 but returned to

active status when made Colonel of the 41st Regiment of Foot, 13 January

1790. He was made Lieutenant General, DD MM 1796. On 26 July 1799, on the

death of his brother, Stirling succeeded to the baronetcy of Ardoch. On 1

January 1801, Sir Thomas was made General. See DNB XVIII: 1270-1271;

Ferguson: Scots Brigade, Richards: The Black Watch at Ticonderoga: 80-81

and Valentine II: 828-829.

James Rumsey

was the Stirling expedition's commissary or supply officer

and only member of that expedition to return to the Illinois country. He

is mentioned twice in Kirkwood's Memoirs: first, as the officer who

volunteered to carry a letter overland from Fort Massiac to Fort de

Chartres warning the French commandant of the Highlanders' pending arrival

and requesting guides; and secondly, as the officer who got lost in the

canebreaks for three days at Christmas 1765. Rumsey first appears in the

British army as a commissioned Lieutenant in a new-raising Independent

Company of Free Negroes, 4 February 1762, in the West Indies, and a mere

five months later (no doubt due to the high casualty rates from disease at

Havana) was transferred to a lieutenantcy in the 77th or Montgomerie's

Highlanders, 27 July 1762.

When the 77th was disbanded, 24 December 1763, Rumsey went on half-pay

until he was able to exchange into the 42nd Regiment as an Ensign with

seniority as a Lieutenant dated 17 March 1764. It was not uncommon after

the 1763 reductions for the army to give preference to half-pay

lieutenants who were willing to serve in a battalion at an ensign's pay

whilst preserving their seniority in the higher rank.

Rumsey abruptly retired from the army 27 August 1766, a month after his

return from the trip down the Ohio and Mississippi, "drowned in debt" and

"obliged to sell out" according to his commanding officer, Thomas

Stirling.(SJ, 22.) His Illinois experience however soon landed him a job

with the trading firm of Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan, [BWM] in

Philadelphia. This company, assisted by the cooperation and connivance of

George Croghan, deputy Indian superintendent under Sir William Johnson,

moved to seize a virtual monopoly of the Indian trade of the Illinois

country that Rumsey had just left. In this "Grand Illinois Venture,"

Rumsey accompanied George Morgan, the third and youngest partner in BWM,

to the Illinois country in 1766 in the capacity of assistant.

However, difficulties with the military, growing competition from other

traders, and charges of unscrupulous business practices brought about a

decline in the company's fortunes by 1767, and the partners went into

voluntary receivership with their creditors administering the business. By

1768. Rumsey was putting down his own roots for Captain Gordon Forbes,34th

Foot ,commanding at Fort de Chartres reported to general Gage in June 1768

that he had "given leave to one Mr. Rumsey, Late a Lieutenant in the 42d

Regiment (who has the honour of being known to your Excellency) to settle

upon a Spot of Ground near Kasakaskies; it has been forfeited to the King

ever Since we have been in possession of this Country."

In 1772 the firm withdrew from the Illinois venture, and the process of

liquidation continued until about 1776.

James Rumsey managed affairs for the Illinois branch during Morgan's leave

of absence when the firm began to flounder in 1770. Although he was an old

friend of Morgan, he jumped ship and accepted an offer to become the

secretary of Lieutenant Colonel John Wilkins, commanding officer of the

18th Foot headquartered at Fort de Chartres, Morgan's enemy. Rumsey then

became a partner of merchant William Murray, in competition with his old

employers and it was through their local trading firm that remaining

goods of BWM were liquidated from 1772-1776. In April 1772, Rumsey's

patron, Lt. Colonel Wilkins asked for leave to settle some disputes with

the local traders who had sent their petitions to General Gage complaining

of Wilkin's conduct.

The Royal Irish left the Illinois Country forever in May, 1772 leaving

behind a small temporary garrison of a light infantry company and half of

the lieutenant colonel's company in Kaskaskia, the principal trading

settlement. Later in the month, a group of Chickasaws raided the store of

Rumsey and Murray at Kaskaskia, and they were forced to call upon the

remaining garrison for help. At the end of the affair, several warriors

were killed and one taken prisoner. No further record of Rumsey

Gordon Forbes to Gage(Fort Chartres, June 23, 1768) in William L.

Clements Library, Gage Papers, American Series, vol. 78, 1-4;

psmith@42ndRHR.org

http://www.42ndRHR.org

Last modified: April 12, 2021

Copyright © 2013

Preston M. Smith and the 42nd Royal Highlanders, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Blog |

Main Page |

Pipes |

Fifes |

Drums |

Dancing |

Escort to the Colors |

Pictures |

Booking the 42nd |

History |

Maps |

DeChartres |

Ireland |

Uniforms |

Warrants & Inspections |

Rev. War Officer Lists |

Links |

Bibliography |

42nd Recordings |

42nd Merchandise |

Griffin Endowment |

Scottish Society |

Burns Supper |

Forfar Bridie Booth |

The Whole 9 Yards |

Golf Outing |

2013 Tour of Scotland

|